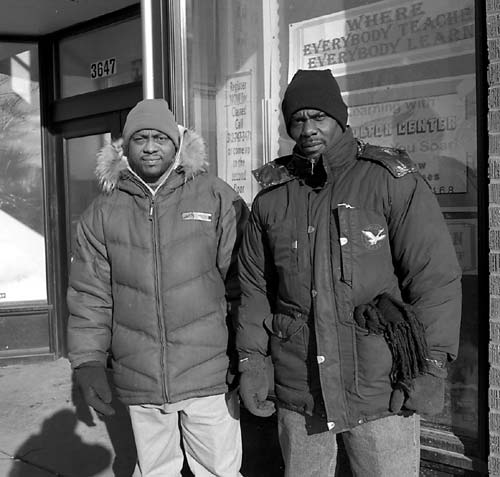

Morton Walker and Shawn Baldwin in front of the Chicago Bee Branch Public Library where they were arrested on January 7 as part of the "State Street Coverage Initiative.”

On Tuesday, January 7, Morton Walker and Shawn Baldwin went, as they often do, to the Chicago Bee Branch Public Library at 3647 South State across from Stateway Gardens. They are among the regulars at the Bee Branch. Both are 40 years old. Morton, who grew up at Stateway, was released from prison in 1999, after serving nine years of a twelve year sentence for criminal sexual assault. (The Illinois Supreme Court overturned his conviction and ordered a new trial; he accepted a plea bargain and immediate release.) Shawn, too, grew up in the neighborhood. Currently homeless, he stays at a nearby shelter. He and Morton became friends over the last few months, as they worked side by side at the computer terminals in the library and shared their knowledge of the Internet.

“He learned from me, and I learned from him,” said Shawn. “That’s how we got to know each other.”

Morton and Shawn feel welcome at the Bee Branch. “Everyone knows who we are,” said Shawn. He particularly appreciates the hospitality of the security guard Miss King. “She knows who are the troublemakers and who are the ones who come in there to get information from the computers or from the library itself.”

One of the attractions of the Bee Branch, according to Shawn, is that “they have Dell computers with Pentium 4 processors.” The two men use the computers to check their e-mail, to search for jobs, and to explore the Internet. Morton likes to play chess on the computer. Shawn has a passion for the game SimCity.

For Morton, the Bee Branch has provided a setting in which he can continue the education he advanced in prison. While incarcerated, he got his GED. He went on to get an Associates Degree in General Education, an Associates Degree in Liberal Arts, and an Associates Degree in Science. Then he began to take college courses in a program offered by Roosevelt University. When he was released from prison, he had enough credits for a BA degree. The administrators of the program arranged for him to graduate with the Roosevelt University class of 2000. Oprah Winfrey was the graduation speaker. The title of his senior thesis was “Urban Renewal: a minority nightmare.”

En route to the library the morning of January 7, Morton had an encounter with the police. He and a friend, Mike Fuller, were walking on State Street, when an unmarked police car driving on the sidewalk outside the grocery store at 37th approached them. Three plainclothes officers got out and ordered them to put their hands on the car. One officer checked their ID’s, while the other two searched Morton and Mike. The officers, Morton later learned, were from the Special Operations Section of the Chicago Police Department. The one who searched him was named Milton.

Once their names had been run and had cleared, Officer Milton said, “I’m gonna give you guys a pass today, but I don’t want to see you out here no more. Tell your buddies:State Street is closed. There’ll be nobody walking or standing on State Street. From 35th to 39th is off limits.”

“We thought it was because the president was in town,” recalled Morton. President Bush was to announce his plan for massive tax cuts before the Economic Club of Chicago at the Sheraton Hotel that afternoon.

Morton asked Officer Milton whether that was the reason they were clearing the street.

“No, this is from now on,” he replied. "There’ll be no more standing on State Street. Go over to Federal, if you want to hang out.”

“There’s nothing over there but a bunch of drug dealers,” said Morton.

“We’re not concentrating over there. We’re concentrating on State Street,” said Milton. "We’re shutting it down.”

When the police released him, Morton proceeded to the library and signed up for a computer. While awaiting his turn, he read newspapers and magazines. It is perhaps a comment on the daily realities of being a black male on the streets of a public housing community that he didn’t mention his encounter with the police to Shawn. “It was nothing," he said later, "to bring out in conversation.”

Morton and Shawn were signed up for computers from 1:00 to 3:00 pm. At 12:50 pm, they stepped outside to share a cigarette—they had one between them—before beginning their computer sessions. As they stood in the doorway of the public library, Officer Milton and his crew drove up on the sidewalk, ordered them to put their hands up against the wall, and handcuffed them.

Morton and Shawn tried to explain that they weren’t allowed to smoke in the library, that they had just stepped outside for a few minutes.

“We got a place where you ain't gonna be able to smoke,” said one of the officers.

“You didn’t go to the library when you was in school,” Officer Milton taunted them. “What are you doing there now?"

They were placed in a police van. Three other men were arrested on State Street at the same time. All were middle-aged. The police joked that they had arrested “the gray-haired gang.”

They were taken to the Second District police station at 51st and Wentworth, where they were held for fifteen hours. Arrested at 1:00 pm, they were not released until 4:00 am. While they were held, others charged with relatively serious crimes came through and were released.

“Everyone in the police station knew who we were," said Morton. "So they must have told them, 'Let those guys sit for a while.'"

Morton and Shawn were charged with disorderly conduct under a city ordinance that defines the offense as follows:

Fails to obey a lawful order of dispersal by a person known by him to be a peace officer under circumstances where three or more persons are committing acts of disorderly conduct in the immediate vicinity, which acts are likely to cause substantial harm or serious inconvenience, annoyance or alarm.

The arrest report in Shawn's case states:

A/Os [arresting officers] observed Shawn Baldwin on several occasions loitering in the 3600 S State street area with several other male black subjects. A/Os did advise subjects to disperse several times to no avail. A/Os placed above offender under arrest.

What is striking about this report is that the arresting officer makes no effort to present the offense—the acts "likely to cause substantial harm or serious inconvenience, annoyance or alarm"—as anything more than the presence of black males walking and talking on the street. Was that the crime for which Morton and Shawn were arrested: being black and poor and visible on South State Street?

* * * *

What Morton and Shawn didn’t know at this point was that their arrest on the threshold of the public library was not an instance of abusive police practices by individual officers. It was, rather, a result of an order that had come directly from the highest authority in the City—the Mayor. It was not a matter of individual officers casually disregarding citizens' constitutional rights. It was, and is, the official policy of the City: the “State Street Coverage Initiative.”

Since January 7, there has been a continuous police presence on the street—all three "watches," around the clock, seven days a week. At times, I have observed as many as five police cars, with their blue lights flashing, deployed on the block-and-a-half stretch across from what remains of Stateway Gardens. Relocation and demolition have reduced this public housing community to two buildings—a ten-story building across from the public library on State and a seventeen-story building on Federal. The increased police presence has been directed not at the drug trade in the open air lobbies of the two high-rises but at the presence of community members on the street. Officers assigned to the State Street Coverage Initiative have been making arrests for loitering and giving tickets for jaywalking, within sight of open drug dealing.

Conversations with police—from administrators to officers on the street—yield a remarkably consistent account of the origins of the operation: En route to or from a function somewhere on the South Side, Mayor Daley was driven down State Street. From his limousine, he saw people hanging out on the street. He did not see any police. Upset, he ordered Police Superintendent Hillard to clean up South State Street. The rationale for the mayor’s directive, as it was understood and filtered down through the ranks, was not to protect neighborhood residents from crime but to make the area attractive to developers.

A week and a half after the launching of the State Street Coverage Initiative, Pete Haywood, was standing on State Street by the Stateway Gardens management office. A lifetime resident of Stateway, Pete is a member of the resident council and was most recently employed by the property management firm. A police car containing three white officers drove up.

“What are you doing standing there?” one of the officers asked.

Before Pete could respond, the officers continued.

“Don’t you know?” he said. “This ain’t CHA no more. It’s the white man’s land now. You can’t stand there.”

Photographs of State Street taken between January 13th and March 1st, 2003.